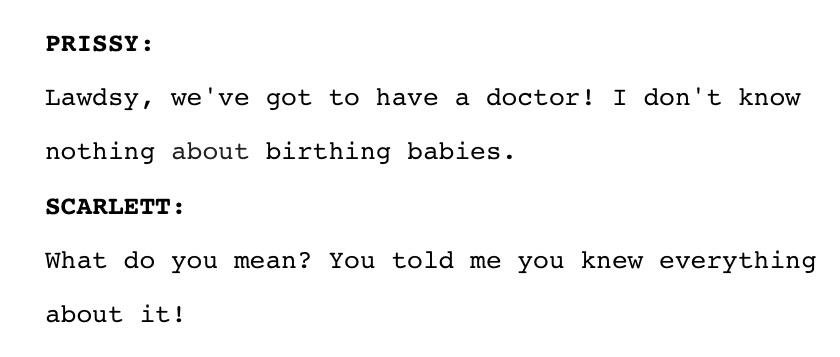

Don’t know nothing ’bout birthing babies

I AM EATING my crew meal in the aircraft galley behind a curtain, standing up over the metal counter. The movie is playing, the cabin quiet on this night flight to Korea. A young woman approaches and pushes aside the galley curtain. “May I help you?” asks my coworker Tom. “No. I want to talk to her,” she says pointing directly at me. I put down my fork, step outside the galley, ask how can I help her. “I think I’m having a miscarriage,” she tells me.

We are somewhere over the Pacific Ocean, hours from landfall. I page for a doctor and a military corpsman responds, fresh from a rotation in OB-GYN. My passenger is in good hands.

Hours later, in my hotel room in Seoul, Tandrea, a flight attendant from my crew calls me on the phone. She tearfully tells me she thinks she’s having a miscarriage. I call a cab, take her to the Yongsan Army Base emergency room, stay with her until she is given the OK to leave.

One week later, I am called at home by Flying Tigers crew scheduling. How quickly can I get to Seattle? A flight coming from Japan has diverted because a volcano erupted in Alaska, closing the Anchorage airport, the originally scheduled stopover on the way to Los Angeles. Now the plane is in Seattle and the crew has run out of duty time, the number of hours they are legally allowed to work. A new crew of flight attendants must be hurriedly assembled to replace them.

A skeleton crew and I show up at SeaTac airport. We hurry to our gate. 400 passengers are milling around, waiting for us, tired, annoyed, ready to continue on to LAX. I see paramedics attending to a passenger lying on the carpet. I’m the flight attendant in charge that day, so I walk right up, ask what is going on.

“She’s having a miscarriage,” the paramedics tell me.