Locked up abroad: Suriname

Paramaribo, Suriname

I AM HANDING my passport to the official seated in a cubicle behind a glass window in the airport in Paramaribo, Suriname. He dismissively flips through the pages then tells me I need to fill out an online customs form. I look bewildered. I had checked entry requirements before I left for this tiny country at the top of South America and all I saw for Americans was ‘visa on arrival’. The official tells me two women standing near the windows with iPads will fill out my customs declaration online for me. They do and I again approach the window, this time with my digital customs declaration on my phone.

Then he asks me, “Where is your visa?“ “Visa?” I splutter. I thought ‘visa on arrival’ meant look at my passport, stamp it and hand it back to me. Apparently not in Suriname! I am informed that I need an electronic visa, not something filled out with a piece of paper and a pen. Suriname is a poor Third World country, only 50 years independent, the airport a collection of drab concrete buildings with no air conditioning. They require a visa filled out electronically?? I try to pull up and fill out the online form using my iPhone and also my iPad, but I can’t. The internet in the airport is weak as I repeatedly click on ‘DISCLAIMER’, the last page of the visa application, but nothing happens. I try again and again, with no success. There are no ladies with iPads to assist me this time.

A military policeman, ribbons and insignia decorating his chest, comes over to the window to find out what is going on. He tells me he’s the supervisor. I find out later he is a sergeant major, which is a high enlisted rank in the military in the States as well. A discussion ensues about my lack of the visa necessary for entry to his country and he demands I surrender my passport. I start to panic.

My heart pounding, I lower my voice and start politely calling him Sir. I really have no choice as he is the authoritative boss and I am a little nothing in this country. All I want to do is watch giant sea turtles nesting on the beach and buy some handicrafts. Another military policeman suggests they just take my $58 visa payment and send me on my way, but the sergeant major immediately and emphatically says NO! He does not want his authority questioned by either me or his subordinates. I realize this has now become a pissing contest and he is determined he will win. The American (me) will lose.

I have no choice so very reluctantly, I hand over that valued document, my US passport. He gives me a little scrap of paper with a handwritten address on it and tells me to go to the military police outpost tomorrow. I collect my checked bag from the now-deserted baggage claim and take a taxi to the hotel, comforting myself with the thought that Paramaribo is the capital city and surely there is a US embassy here just in case everything goes really sideways.

At the hotel I ask if I can use their desktop computer to try and fill out the visa form but not on their desktop, nor on my iPhone or my iPad using the hotel’s WiFi, am I able to complete the electronic form. I give up. I have a city tour arranged the next day and I’m going to have breakfast in the hotel, take my little tour and enjoy my morning despite this rocky start. Afterward I will go to the military outpost to get my visa and retrieve my passport.

I go up to my room and post on Facebook what has happened, in a funny, not funny way. I immediately get comments and advice from my worldly, well-traveled friends. An Israeli friend in Jerusalem sends me a private message. He has a ‘friend’ in Suriname he can contact who can help me. I am not allowed to contact this mysterious man directly but my friend Tzachi will get in touch with him and this nameless, faceless, anonymous stranger will help me. I have visions of Mossad swooping in to rescue me.

In the morning, my guide Pinelli shows me around the city, filled with pastel gingerbread houses and churches from Suriname’s Dutch colonial past. We wander through the colorful Maroon Market, established by the maroons, descendants of slaves who 150 years ago escaped from plantations and established communities in the jungles of Suriname, communities which thrive to this day.

Some call this marketplace the Witches’ Market. Huge piles of medicinal herbs and plants gathered in the jungle are offered for sale here. Potions and lotions in jars and bottles are displayed on folding tables, the vendors fanning themselves in the morning heat. Pinelli shows me a bottle of anaconda oil used to soothe aching joints. He points to little vases of feathers sitting on each table, not for sale, not for decoration, but obviously placed there carefully for something else. He doesn’t elaborate. Witches don’t have to explain.

Afterward my guide drives me to the military outpost. I check in at a huge concrete gate manned by two uniformed soldiers who peer at me through ominous window slits. They motion me inside a building where I sit on a hard wooden bench in the hallway. Eventually a military policeman gives me my passport and sends me to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, an official sounding name for a modest little cottage that hardly looks like a government building. There I am told I must go to a specific bank to pay my visa fee and then return to the Ministry with the receipt.

There is a problem, however. It is 1 o’clock and I am told the bank closes for the day in 15 minutes. There is not enough time to drive over to the bank, park, go inside, complete the visa formalities, pay the fee, get a receipt and drive back to the Ministry. I have also been informed the Ministry closes for the day in 30 minutes. There is no way I can possibly accomplish all this while driving back and forth in the noonday traffic.

Discouraged and annoyed, I decide I will go back to my hotel and forget about getting a visa. What are they going to do? Show up at the hotel and arrest me? Throw me in jail for illegal entry? Slap me with a fine as I leave the country? I’ve had enough. I smile, thank the official, put my passport in my bag and turn to leave.

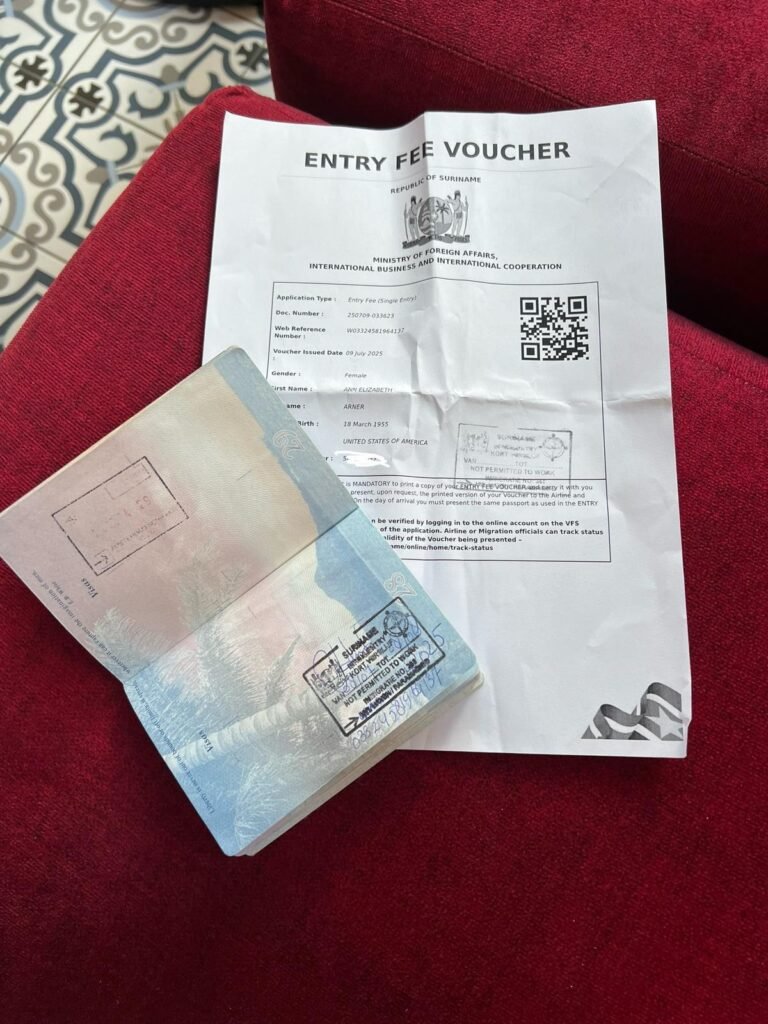

Suddenly a consular official brings his laptop into the lobby and tells me he will fill out the form for me. I can tell he is not happy as closing time is in 20 minutes and he surely has things on his desk to complete. He was probably looking forward to going home for the day, having lunch with his wife, perhaps taking a nap. He kindly fills out the form and enters my credit card payment. I finally receive my visa and now I’m legal!

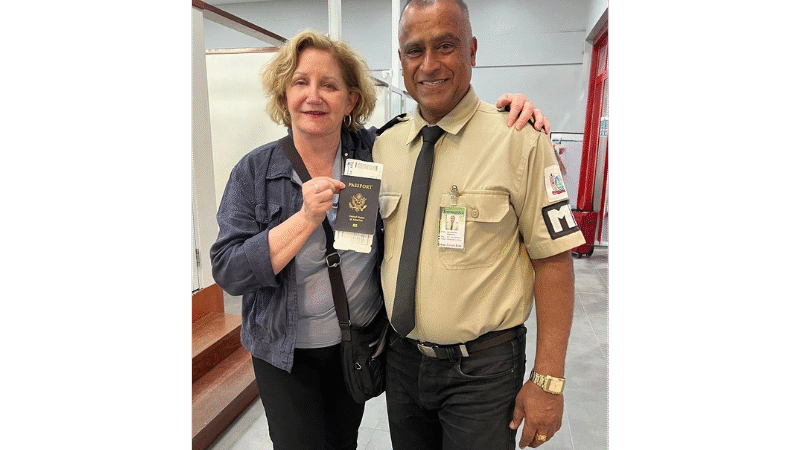

Two days later as I leave Suriname, the airport is chaotic. People are checking luggage, standing in line, waiting for officials to validate passports with exit stamps. Suddenly I see the military policeman, the sergeant major, who gave me such a hard time at the airport when I arrived. I have to admit, he is a very hands-on supervisor. He is walking around the departure hall, peering over the glass partitions, entering the cubicles, standing with his hands on his hips, carefully ensuring all departing passengers are properly processed. I sneakily take a few pictures of him.

Suddenly he sees me and smiles in recognition. He walks over and solicitously asks if I got my passport back. I smile and say yes, everything went just fine, and could I take a photo with him? He consents. I ask his name (Dennis) and we look at the camera, the two of us smiling broadly, me holding that precious document, my US passport.

Then Dennis asks, “When are you coming back to Suriname?” I answer vaguely, “Maybe next spring.” Dennis brightens. “Next week?” he asks. “I give you my number and you call me!” He misunderstood me. “No, no,” I say hastily. The last thing I want is Dennis for my boyfriend. “Maybe next spring” Or maybe never.

Dennis certainly has a funny way with women. This is how he impresses a girlfriend prospect?

Well told, Ann. You sure can put a reader right into the situation. You are so brave.

Deb