Progeny of the prodigy

I AM FLYING as a passenger tonight from Atlanta, Georgia, to Boston, returning excited and energized from a 2-day company presentation. I am seated next to an ordinary guy in his 40s, kind of scruffy looking, a faint smell of liquor about him. We start talking. A chef in the Merchant Marine, he is returning home from a voyage to China, among other places.

I know the flight attendants working this flight and they offer me a free cocktail as they serve beverages. I ask my seatmate what he drinks (merlot) and give the free drink to him. I ply him with all sorts of questions about China and his trip. I’m very curious about Chinese food there versus Chinese food here. I ask about meals onboard ship and the logistics of cooking at sea.

He tells me at the end of every voyage, leftover food is given to another ship in port or to crewmembers to take home. He shows me his excess baggage receipt totaling $175 for shanks and roasts and various cuts of meat, checked on this flight in the cargo hold. “That will be some of the most expensive lamb you’ve ever eaten,” I laugh, and ask about packaging. “Lots of dry ice, frozen solid,” he assures me.

I see his name on the receipt, Joseph Emidy, kind of an unusual name. “Hungarian?” I ask. He looks at me rather curiously and slowly says “No, it’s African.” “Africa is a big place,” I reply and ask him where in Africa, thinking his family are white Afrikaaners from South Africa or Caucasian settlers from Rhodesia. He tells me the Guinea Coast, and his ancestor was a black African slave. I look at him in disbelief. My blue-eyed seatmate Joe is as white as me.

The flight attendants pull their beverage cart past our seats on their return to the galley, and offer me another free drink. I immediately order a second merlot for my new friend. “Do tell,” I say, and the most amazing story unfolds over the next hour of the flight.

Joe Emidy’s ancestor, Joseph Antonio Emidy, a young African man living in Guinea on the west coast of Africa in the late 18th century, was captured, enslaved, shipped off to Brazil. His Portuguese owner did not force him to work outside in the fields but rather used him as a house servant. Somehow it became apparent that this slave had musical talent and ability, and he became an accomplished musician, tutoring the children of the household.

The slaveowner then took Joseph to Portugal, where he became a violinist with the Lisbon Opera, as well as a teacher and composer of music. One night a British ship captain, enthralled after hearing the slave’s performance at the opera house, shanghaied Joseph and forced him to become a ship’s musician on his frigate for several years.

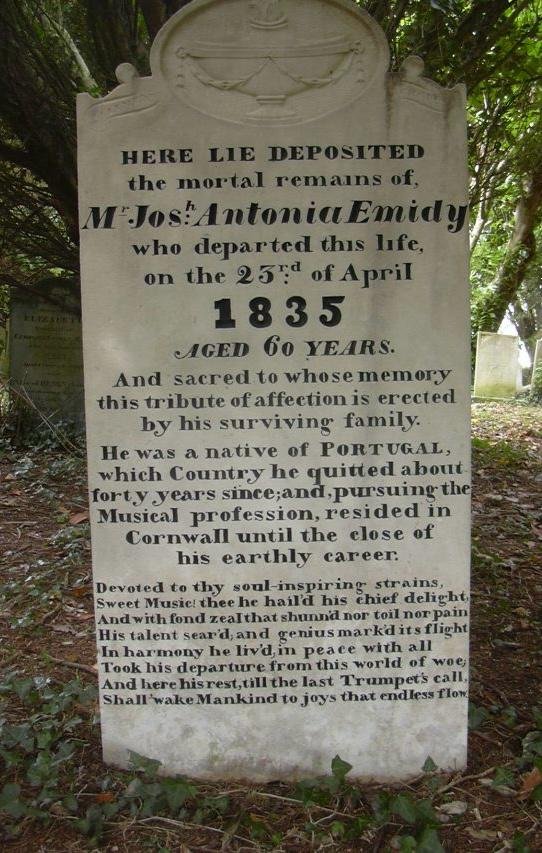

Eventually, the British sea captain granted Joseph his freedom and he settled in Cornwall, England. There Joseph Emidy, native of the Guinea Coast, enslaved for most of his life, a man without a country, without personal freedom or the ability to make his own choices and decisions or to control his destiny, was suddenly free. He married an Englishwoman and continued to teach, compose and perform music for the rest of his life.

My seatmate Joe told me none of his illustrious ancestor’s musical compositions have survived, and there is only one known painting of him.

“What a story!” I exclaim. That a slave could achieve such prominence, that the story of this slave has been told and retold for generations to hear and remember. “You are his namesake,” I say, and ask if he has a son to call Joseph. “No, but I do have two daughters who are very proud of their lineage,” Joe replies.

This extraordinary story fascinates me, and I want to know more. Later, searching the internet, I find the only painting of Joseph Antonio Emidy playing his violin. I see photos of descendants from 100 years ago. I see the African heritage blur in their faces as they marry and raise families in England, in America, in Brazil, in Canada. Many of them become musicians.

That night, Joe Emidy confided in me that he doesn’t usually go into detail about his heritage with strangers. It’s too complicated, too unusual, but he saw in me a willing listener.

Two bottles of merlot and a darkened, hushed airplane cabin helped as well.