Written In The Stars

Varanasi, India

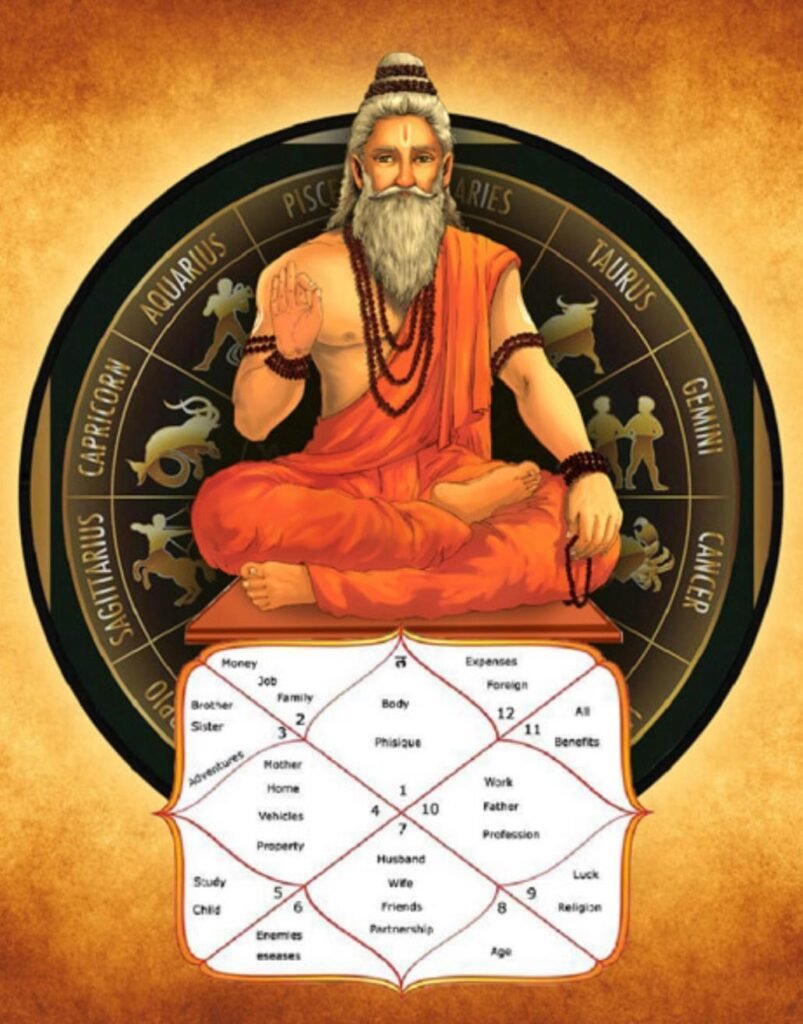

I AM HAVING my palm and astrological chart read in Varanasi, India. A Brahmin priest, a professor of astrology at the University of Benares, is doing the honors. He has a distracting red mark on his forehead and long wild hair. His name is Dr. Prasad and I am rather flattered that this illustrious scholar has consented to read for me.

I am sitting in his office. A neon light fixture casts a cold blue glare on the astrological chart in his hand. A mouse skitters across the floor. A big rat would’ve given me pause, but not this little field mouse.

He tells me nothing of interest, just vague predictions of health, wealth, satisfaction. “All will be well eventually,” he assures me, writing down calculations he has gleaned from the position of the moon, the sun, the planets, on the day and hour of my birth. He writes with a flourish in an orange pen on a paper that will be mine to keep.

He examines my palm. He marks my hand with his orange pen. There is a Shiva lingam in the crease, an auspicious sign. I have the mark of the god‘s penis on my palm. There is much reverence of the lingam in India, and almost any upright object is considered a manifestation of the god Shiva’s manhood. People caress it as they walk by, or decorate it with offerings of rice, flowers, vermilion paste.

He checks the creases on the side of my hand. “You have three children,” he states. “No, I don’t,” I say, looking him steadily in the eye. “Only one.” He squints, looks at the three creases again, frowns, holds my hand up to the light, curls my fingers slightly and scowls.

I’ve invented a husband and a son for my stay in India. I learned long ago that a woman my age who is single is an oddity in the Third World, and a childless woman is an object of pity. I dislike being asked, “Do you have children?” and when I answer “No,” the next question is a dismissive, “Why not?” So I’ve created a husband who does not like to travel and a university student son, age 20. Boys are revered in most parts of the world, so this imaginary son gives me a little status.

Dr. Prasad asks me if I have “missed“ which I take as a euphemism for miscarriage. “No,” I murmur. “Well,” he backtracks. “You will adopt two children, perhaps when you are working for an NGO.” I smile. “That’s a possibility,” I say, though I have absolutely no intention of complicating my life with children, neither mine nor anyone else’s. “I have done a lot of humanitarian work,” I tell him. Dr. Prasad brightens considerably. “Yes! You will adopt two children!” He beams with this pronouncement. He closes our session by asking if I have any questions. “My mother,” I say. “How about my 85-year-old mother?”

His answer is cryptic, but believable enough to give me chills. “If she survives this next year, she will live four more years,” he intones. I thank him, pay my rupees and leave.

Why should I believe this ominous prediction, when everything else he has told me is either ridiculously vague or flat out wrong?